Individual. These are patient-level factors that may include challenges and delays in seeking or accessing care, and difficulty in adhering to treatment plans.

In the Emergency Department, individual, interpersonal, and institutional biases can affect decision-making about patients at the very beginning. Triage nurses are responsible for the initial assessment of patients and assigning an acuity level.

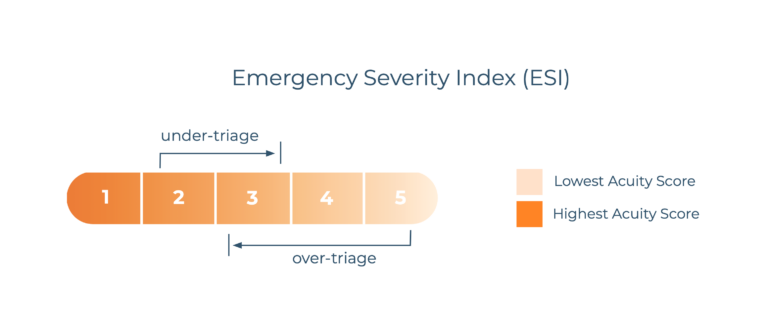

Most EDs in the United States use a standard 5 level triage system such as the Emergency Severity Index (ESI). In practice, however, the assignment of patient acuity varies among emergency nurses and in their respective emergency departments. Patient acuity decisions are sometimes made without basic physiologic data and can vary based on nurse skill and the social context at the time of triage. Not surprisingly, ESI and other triage systems are highly prone to individual, interpersonal, and institutional biases.

This can lead to triage errors, such as under-triage, which is the assignment of an inappropriately low acuity score that can result in dangerous delays of necessary medical care. Biases may also lead to over-triage, which occurs when less critical patients are assigned a higher priority, leading to resource overutilization and delays in providing care for those with more urgent needs.

Specifically, racial, age, and gender bias can impede accuracy in triage decision-making by causing nurses to ignore critical cues.

Hinson (2018) reports that high-risk presentations often went unrecognized across their general population3, while Lopez et al. (2010)4, Schrader and Lewis (2013)5, Puumala et al. (2016)6, and Zook et al. (2016)7, all noted under-triage in minority populations of all ages. Grossman et al. (2014)8 found significant under-triage in geriatric populations. Arslanian-Engoren (2004)9 described poor decision-making about women presenting with chest pain.

Black patients are 10% less likely to be admitted to the hospital.

Black patients are more likely to be assigned lower triage acuity scores (TAS) by nurses than White patients, thus significantly increasing the time they have to wait for treatment. In fact, Black patients are given lower TAS scores than Caucasian patients when they visit EDs during the same time periods. As a result, Black patients on average have to wait 11 minutes longer to be treated than White patients. Research suggests that in comparison to White patients, Black patients are 7% less likely to be assigned an appropriate triage score, 10% less likely to be admitted to the hospital, and are 1.26 times more likely to die in the ED or in hospital.5

Myths around the pain tolerance and decreased sensitivity of Black patients lead to disparities in pain management: Black patients are 14 percent less likely to receive opioid analgesics for traumatic or surgical pain, and 34 percent less likely to receive them for chronic pain. Nursing textbooks also present pain expression as a function of “culture” leaving many nurses with residual stereotypes that can impede pain identification and management.11,12

Institutional disparities in the healthcare system affect care even before the patient reaches the hospital. Among Medicare beneficiaries, while EMS providers transport White patients to the closest reference EDs 61.3 percent of the time, Black patients in the same zip code are taken to these EDs at a 5.3 percent lower rate and Hispanic patients at a 2.5 percent lower rate.

61.5% of White patients are taken to reference EDs

For members of the LGBTQ+ community, the specific impact of biases may be related not just to structural bias and challenges with access, but also negative experiences with use of pronouns, correct gender references, and use of the patients’ name.

LGBTQ+ patients report avoiding Primary Care altogether because of healthcare bar- riers including lack of quality health insurance, fear of judgment or poor treatment, or past experiences of discrimination or harm.14 When patients do seek medical care in the ED, they often report negative experiences, including being misgendered, misnamed, mocked, or refused care by healthcare providers.

Cognitive errors can influence clinical decision making and contribute to inequity when delivering healthcare services. Some of the most common cognitive errors include:

- Premature closure. This error happens when a clinician jumps to conclusions about a diagnosis without collecting enough data and exploring other possible diagnoses.

- Confirmation bias. When clinicians make up their mind about a diagnosis, and they only consider information that affirms that opinion.

- Aggregate bias. This cognitive error describes when clinicians believe aggregate population data applies to an individual patient they’re working with. This error can lead to problems like the wrong types of tests being ordered to diagnose a patient.

- Affective errors. Affective errors occur when a clinician’s personal feelings get in the way of making sound medical decisions. This

can happen when a clinician associates positive or negative feelings with a patient. - Ascertainment bias. This occurs when a clinician’s previous experiences with a patient shape their current perceptions, so they make decisions based on past expectations rather than the present circumstances.

- Anchoring. Anchoring is the practice of giving the entire weight of a diagnosis to initial impressions without considering new information that comes up during the diagnostic process.

- Diagnostic momentum. This happens when a patient has been

given a specific diagnosis and it becomes more and more difficult

to change this label even if new information becomes available.17,18,19,20,21

- Economic stability. This refers to issues related to employment, income, household expenses, medical bills, and debts.

- Neighborhood and physical environment. Safety concerns are part of this SDOH, as well as the walkability of an area, housing, and transportation.

- Education. The education factor includes literacy, language, and access to education from early childhood education to college and vocational training.

- Community and social context. Social integration and engagement, support systems, and discrimination.

- Food. Hunger, food insecurity, and lack of access to healthy food have a negative impact on healthcare outcomes

- Healthcare system. This SDOH includes healthcare coverage, quality of care, and provider availability and cultural and linguistic competency.

Without relevant data, it’s next to impossible to address biases in care

delivery. Facilities should collect data on patient demographics and outcomes, paying particular attention to outcomes from underserved populations in order to fully understand where inequities occur. Also, reviewing statistics about the outcomes of patients on a city, state, and federal level can provide further insights on shortfalls in care under- served patients receive.

Healthcare professionals cannot address the barriers patients must

navigate unless they understand what those obstacles are. To deter- mine where staff education should be directed, facilities can conduct assessments that measure staff knowledge of the SDOH of under- served patients. This can begin a dialogue about these issues, so providers feel more comfortable addressing them in collaboration with patients when they come up.

- hiring more staff members from diverse communities

-

teaching employees how to recognize their bias and developing strategies to mitigate them

- opening and maintaining a dialogue with minority groups to understand their concerns

- implementing and maintaining a plan to address the concerns of these communities

- Conscious bias

- Unconscious bias

- Microaggressions

- Systemic discrimination

Newer technology including those built with artificial intelligence (AI) such as KATE™, can mitigate bias in clinical decision making upon the patient entering the emergency department at triage since it was designed to be blind of race and socio-economic factors. Standardizing care on the front end of the hospital can be useful to decrease the impact bias has on the patients’ plan of care.

In addition to mitigating bias, AI technology, such as KATE improves triage accuracy for patients with varying levels of acuity regardless of race, by as much as 93%.

The benefits of standardizing patient care with technology include:

- Streamline the medical decision-making process by breaking a full decision down to its component parts

- Eliminate the need to rely on judgment calls using limited patient history as a deciding factor

- Separate the patient from potential habitual bias a provider may have

- Allow treatment to be centered solely on specific risk factors

- Reduce the amount of human judgment used when deciding whether the presence of a condition is likely